La Mirande, 2018

La Mirande, 2018On becoming a 5-star boutique hotel, La Mirande has not ceased to be a private house, and is a better guardian of its history than many a palace that is only preserved for visitation or to house a museum.

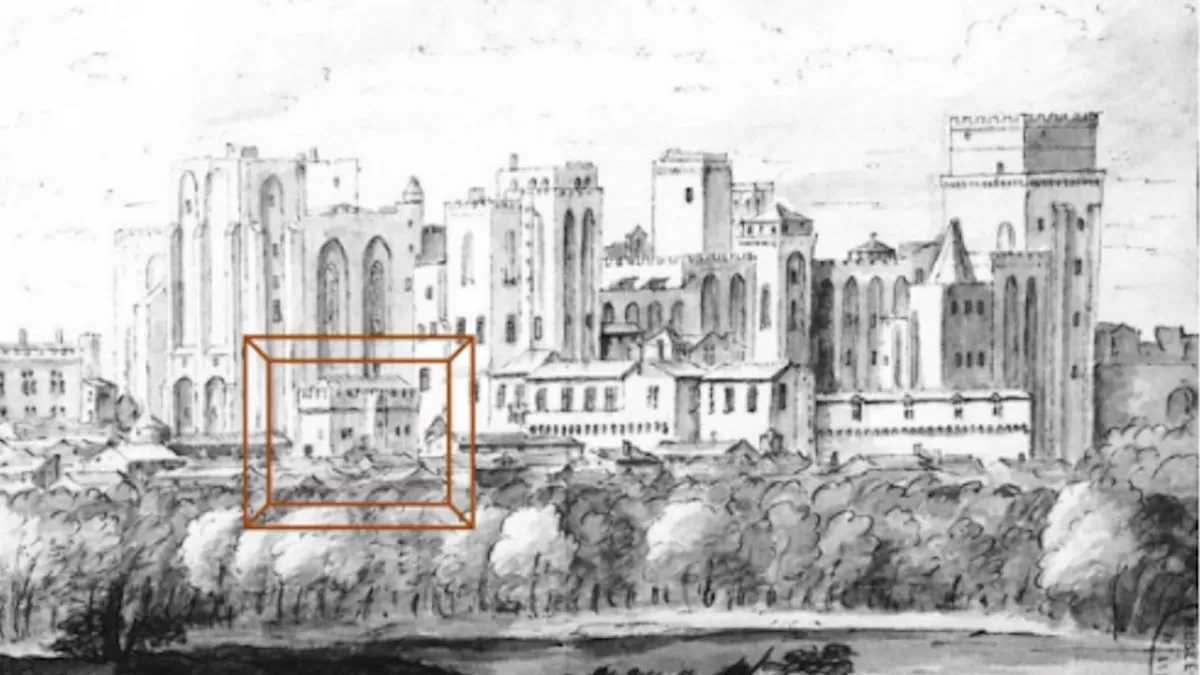

Livery Saint Martial

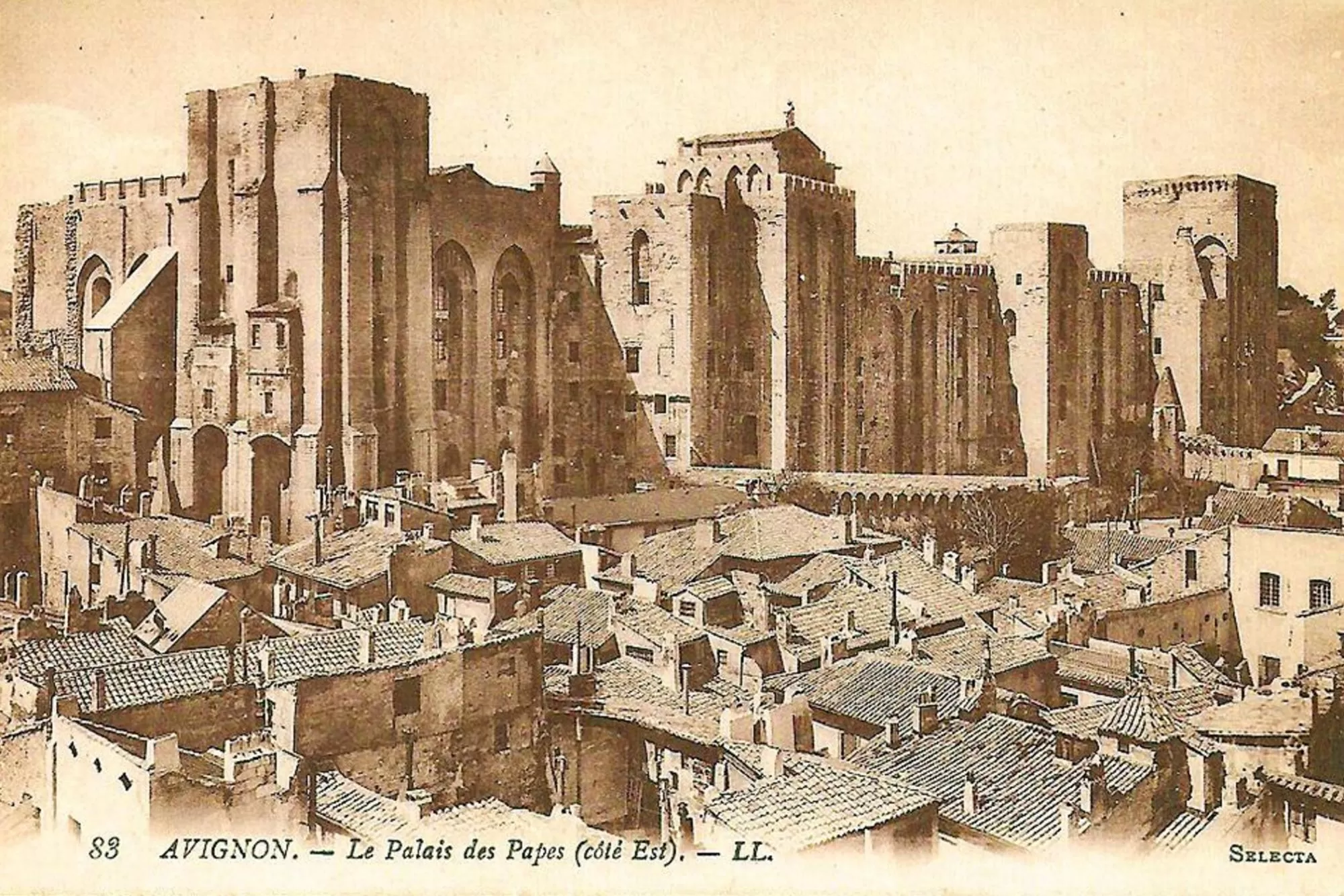

Livery Saint MartialAlthough Roman remains of a public bath still exist, the story begins in 1309 with the establishment of the Popes in Avignon. One of the cardinals accompanying pope Clement V was his nephew, Cardinal de Pellegrue, who built a “livrée”, as cardinals’ palaces were called, in the privileged location of the direct neighbourhood adjoining the Popes’ Palace. Up until the siege of the Popes’ Palace in 1410, when it was partly destroyed, the “livrée” had remained the property of cardinals, in particular Hugues Roger, brother to pope Clement VI, and Hugues de Saint- Martial, the last incumbent. The tower (frame) lost its eminent height but still four levels survive, never completely digested by later adaptations to new ways of living. The main dining room is occupying one of these levels.

In 1653 the remains were sold to a man of law, Claude de Vervins. On his death, his son Pierre, marquis de Bédouin, built the typically classical façade which we see today, the architectural statement of a nobleman’s residence in town or “hotel particulier” as they are named in French. It was designed by the architect Pierre Mignard, son and nephew of Nicolas and Pierre Mignard, painters to King Louis XIV, of whom they painted numerous portraits.

Paul Pamard

Paul Pamard“L’hôtel de Vervin” as it was called then, was the residence of the descendants of Pierre de Vervins until 1796, when it was sold to Jean-Baptiste Bénézet-Pamard, an officer of health. A sign of the times: La Mirande would never again belong to the aristocracy. Renamed as the “Hôtel Pamard”, it will for two centuries be the property of a prominent Avignon family, a member of whom became Lord Mayor and altered the town according to the precepts applied to Paris by Baron Haussmann in the latter half of the 19th century. We can dream today of that long span of years and of the kind of life lived by a bourgeoisie close to Napoleon III, enclosed in the sombre neo-gothic décor inspired by Viollet- le-Duc, amid heavy drapes and 19th century paintings.

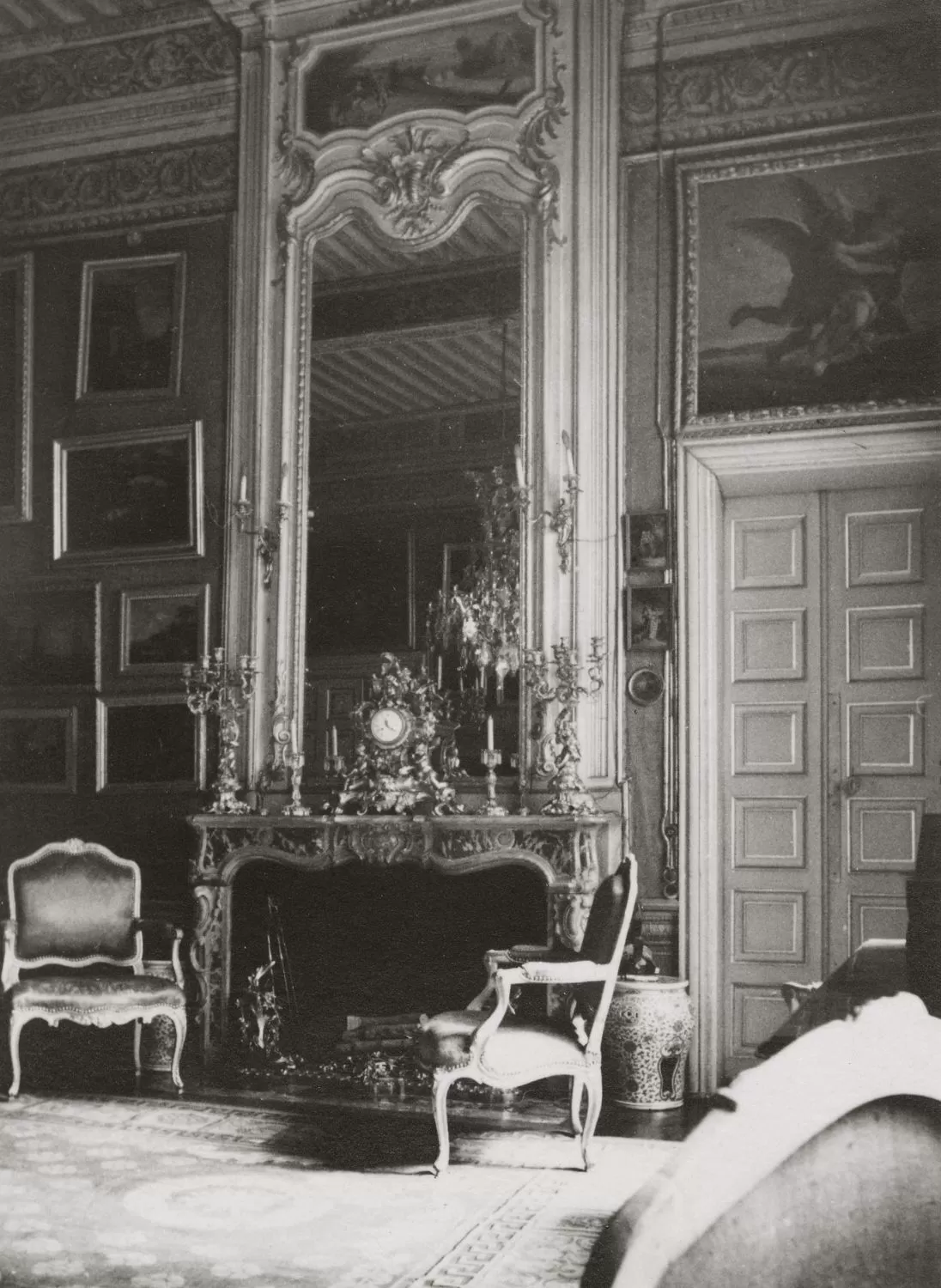

The raison d’être for such large houses dedicated to only one family and their servants vanished in the 20th century. In 1966, as a brief reminiscence of the old times, the state rooms served as location for “La Réligieuse” (“The Nun”) the second feature of New Wave director, Jacques Rivette with Anna Karina in one of her best roles, a movie which ignited a first-class scandal. New York Times

Anna Karina as Suzanne Simonin in La Réligieuse by Jacques Rivette

Anna Karina as Suzanne Simonin in La Réligieuse by Jacques RivetteSombre and secret, such indeed was the tone of the building as the Steins discovered and purchased it in 1987. In three years, they turned La Mirande into something unique, and achieved their aim, which was to create the impression of a private house in which different décors had accumulated over three centuries. They were helped in giving shape to their ideas by the Paris interior decorator, François-Joseph Graf, and the Avignon architect, Gilles Grégoire. The purpose was to obtain an overall harmony out of the coexistence of 18th and 19th century styles, which is infinitely more respectful of the character of the building than earlier arrangements. A unique restoration process was carried out for creating a hotel. The Steins, unfettered by rigid rules, have succeeded in resolving the dilemma familiar to architects responsible for the renovation of historical monuments: what should one keep, what period should be given pride of place? For that which is handed down to us from the distant past is almost always composite. Restoration is not an exact science, but an art, which makes the person carrying it out an artist.

The 5-star boutique hotel is named after the famous room in the Popes’ Palace “La Mirande” set up by the representatives of the Popes to receive the city's notables and high dignitaries visiting the town.

La Mirande was a large rectangular room, 18 m long by 8.5 m wide. There were eight windows and the walls were hung with embossed and gilded leather. It was the main banqueting hall, where balls and concerts were given in honour of distinguished guests, dukes and princes visiting Avignon. At Christmas the Vice-Legat, who was the master of the papal palace when the popes had left, traditionally gave three banquets, one for the clergy, one for the nobility and one for the judiciary.

The memory of this extraordinary place lingered on long after the building was pulled down, giving its name to “Place de La Mirande”, sometimes spelt “l’Amirande”, as a reminder of the origin of the name, the “admirable” hall.

The tremendous force of La Mirande makes itself felt on whoever approaches it from near or from far, an echo of the tumult of the centuries, a resurrection of the splendour of ancient times, reminiscence of the age of enlightenment. La Mirande, 5-star boutique hotel, is a story without end that provokes the imagination. (adapted from a text by Claude Eveno)